MAPrc featured in Qantas Magazine

Qantas has featured an article in their in-flight magazine Qantas - the Australian Way highlighting research MAPrc is conducting on a possible diagnostic tool for mental illness

Thank you to Qantas for supporting research at MAPrc. Please click here to view this article at Qantas Online

BRIGHT IDEAS:

When consulting psychiatrist Jayashri Kulkarni met biomedical engineer Brian Lithgow in a waiting room at Melbourne’s The Alfred Hospital in 2004 something extraordinary happened.

Both Monash University academics had independently gone to see an eminent neurosurgeon to discuss their respective work.

Kulkarni, an internationally recognised researcher and director of the Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre, had long observed the need for an objective diagnostic tool that could be used in psychiatry.

Lithgow, who had worked for hearing implant company, Cochlear, on the trailblazing bionic ear, had years of experience developing measures of the vestibular – or balance – system.

While waiting for the neurosurgeon, the two pioneering researchers started talking. Lithgow described his vestibular test which used an electroplate in the ear canal to measure common disorders such as tinnitus – ringing in the ear – and the disorienting Meniere’s disease. And Kulkarni wondered aloud if the test might be used to identify psychiatric disorders. “Some psychiatric patients describe disordered balance. The vestibular system (located behind the ear) and the limbic system, which controls emotions, are both primitive brain circuitries and are very interconnected,” she points out.Psychiatrists and engineers don’t usually hang out together, note Lithgow and Kulkarni. However, more than seven years on, the upshot of their serendipitous encounter is a diagnostic tool that looks set to turn the typically protracted business of psychiatric diagnosis on its ear.

While waiting for the neurosurgeon, the two pioneering researchers started talking. Lithgow described his vestibular test which used an electroplate in the ear canal to measure common disorders such as tinnitus – ringing in the ear – and the disorienting Meniere’s disease. And Kulkarni wondered aloud if the test might be used to identify psychiatric disorders. “Some psychiatric patients describe disordered balance. The vestibular system (located behind the ear) and the limbic system, which controls emotions, are both primitive brain circuitries and are very interconnected,” she points out.Psychiatrists and engineers don’t usually hang out together, note Lithgow and Kulkarni. However, more than seven years on, the upshot of their serendipitous encounter is a diagnostic tool that looks set to turn the typically protracted business of psychiatric diagnosis on its ear.

EVestG (short for electrovestibulography), a device which detects signals from the brain through the balance organ, is still being tested, emphasise its creators. However, it has the capacity to greatly reduce the time for diagnosis for mental disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia from years to minutes in some cases.

Medico Kulkarni is quick to insist that the technology should not be misconstrued as a replacement for the important doctor-patient relationship. Just as an ECG (electrocardiogram) detects anomalies in heart patients, EVestG produces differing waveform patterns from brain signals. And the need for an objective diagnostic test for mental illness is pressing. The National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2007 found an estimated 3.2 million Australians (20 percent of the population aged between 16 and 85) had a mental disorder in the previous 12 months. Beyond the huge burden on public health systems and society in general is the personal tragedy of delayed mental illness diagnoses, which impact on quality of life through secondary effects, such as the breakdown of relationships, loss of work and deteriorating physical health.

Currently diagnoses are made subjectively from a patient reporting symptoms to a psychiatrist who uses a template of pattern recognition to identify an illness. Studies have show that in complex, episodic conditions, such as bipolar 2, an accurate diagnosis takes an average of around 12 years, says Lithgow. In the absence of a correct diagnosis, it’s also possible that a patient may be given the wrong treatment.

“Psychiatry is probably the slowest branch of medicine to take up new technologies,” asserts Kulkarni. Although over the last five years, a range of technologies have emerged, and brain imaging and genetics research have come a long way. “You can do a brain scan on a person who hears voices, but what you are trying to do is rule out a brain tumour – it’s an exclusion diagnosis.”

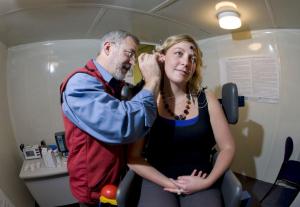

The EVestG test involves placing a probe that feels like a cotton bud close to the eardrum. Sensors in the probe take electroneurological readings which are then amplified 30,000 times. Patients are tilted to 45 degrees to stress their balance systems to record more profound results.

Lithgow and Kulkarni say it took them around six months in 2005, during the first pilot study of 20 patients with depression compared to a control group, to realize they were on to something. Kulkarni let Lithgow test patients without telling him their psychiatric condition beforehand. The pair literally jumped for joy when distinct patterns began to show.

At the outset, the process took an hour and produced vast mathematical data that took around 18 hours to analyse. Subsequently Lithgow wrote an algorithm to speed the analysis, which now takes around 10 minutes.

To date, the researchers have detected clear patterns for schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar affective disorder. Important distinctions, Kulkarni insists, because a bipolar sufferer treated for “normal” depression can be flipped into mania.

Working with a disparate research team of neuropsychologists, psychiatrists and engineers at The Alfred hospital, they have continued to test the integrity of their findings, with support from grants and angel investors to the tune of around A$1 million in funding raised by a purpose-built commercialization company, Neural Diagnostics.

Scientific research is never speedy. Lithgow divides his time between the clinic at The Alfred hospital and Winnipeg, Canada where a team of researchers now have encouraging early data from tests on Alzheimer’s disease, “the biggest growing pathology for the coming generation”.

Along the way, Kulkarni and Lithgow have collected numerous awards, including the top gong from the ABC’s The New Inventors in 2010 for EVestG. However, they’re still a way off taking a product to market. The academic focus remains providing scientific evidence through journal publications, while Neural Diagnostics continues the funding quest. CEO Roger Edwards anticipates around A$10 million will be needed to make the EVestG test widely available and an IPO is anticipated for 2013 to help raise that money.

For some, it can’t come soon enough. Kulkarni says she has been flooded by requests for the test, with the most rampant support coming from people who have experienced mental illness, their carers and families. “People who say it took so long to get a diagnosis and, when I got one, my life turned around.”

The test is also exciting for its further potential.

On the agenda for 2012 is testing for concussive injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder for which measurement can be critical – in football injuries, car accident victims or when a soldier is incapacitated, for instance. It could indicate when it’s okay to send the footballer back on to the field.

The test may also be useful for monitoring treatments, according to Lithgow who has already tested it on patients who are being treated for Parkinson’s disease and depression.

While they may have a way to go, but Kulkarni’s and Lithgow’s auspicious meeting highlights that amazing things happen when researchers collaborate across disciplines and inspire each other to think outside the square. And millions of mental health patients may soon offer thanks to the neurosurgeon who – on the day the inventors met – fortuitously never turned up.